Contributors: Robert Sege, MD, PhD and Dina Burstein, MD, MPH

Positive Childhood Experiences (PCEs) both promote optimal child development and mitigate the effects of ACEs and toxic stress. PCEs allow children to form strong relationships and meaningful connections, cultivate a positive self-image and self-worth, experience a sense of belonging, and build skills to cope with stress in healthy ways. By promoting PCEs, families, providers, and communities can support the development of thriving and resilient children.

The importance of PCEs for healthy development was demonstrated by a study published in JAMA Pediatrics in 2019.1 In this study researchers added seven questions, based on the previously validated Child and Youth Resilience Measure (CYRM-28),2 to the Wisconsin Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) survey. Participants were asked how often as a child they: (1) felt able to talk to their family about feelings; (2) felt their family stood by them during difficult times; (3) enjoyed participating in community traditions; (4) felt a sense of belonging in high school (not including those who did not attend school or were homeschooled); (5) felt supported by friends; (6) had at least two nonparent adults who took genuine interest in them; and (7) felt safe and protected by an adult in their home. The results showed there was a dose-dependent association between the number of PCEs reported and likelihood of adult depression or poor mental health, and that the presence of PCEs mitigated the negative health effects of ACEs. Among individuals reporting having 4 or more ACEs, those who reported 6 or 7 PCEs had a 21 percent incidence of adult depression or poor mental health, compared with those reporting 0 – 2 PCEs, who had an almost 60 percent incidence of depression or poor mental health as adults. This mitigating effect of PCEs held true regardless of the number of ACEs an individual recounted.1

Recent research in the field of neurobiology has shown anatomic and physiologic changes occur in the brain in response to positive stimuli such as intensive meditation training3 and learning to read4. Additional research has demonstrated that the brain shows growth and functional changes correlated with stroke recovery5 and emotional healing following a significant traumatic event.6,7 These studies, as well as other emerging research, present a plausible biologic mechanism of action for PCEs.

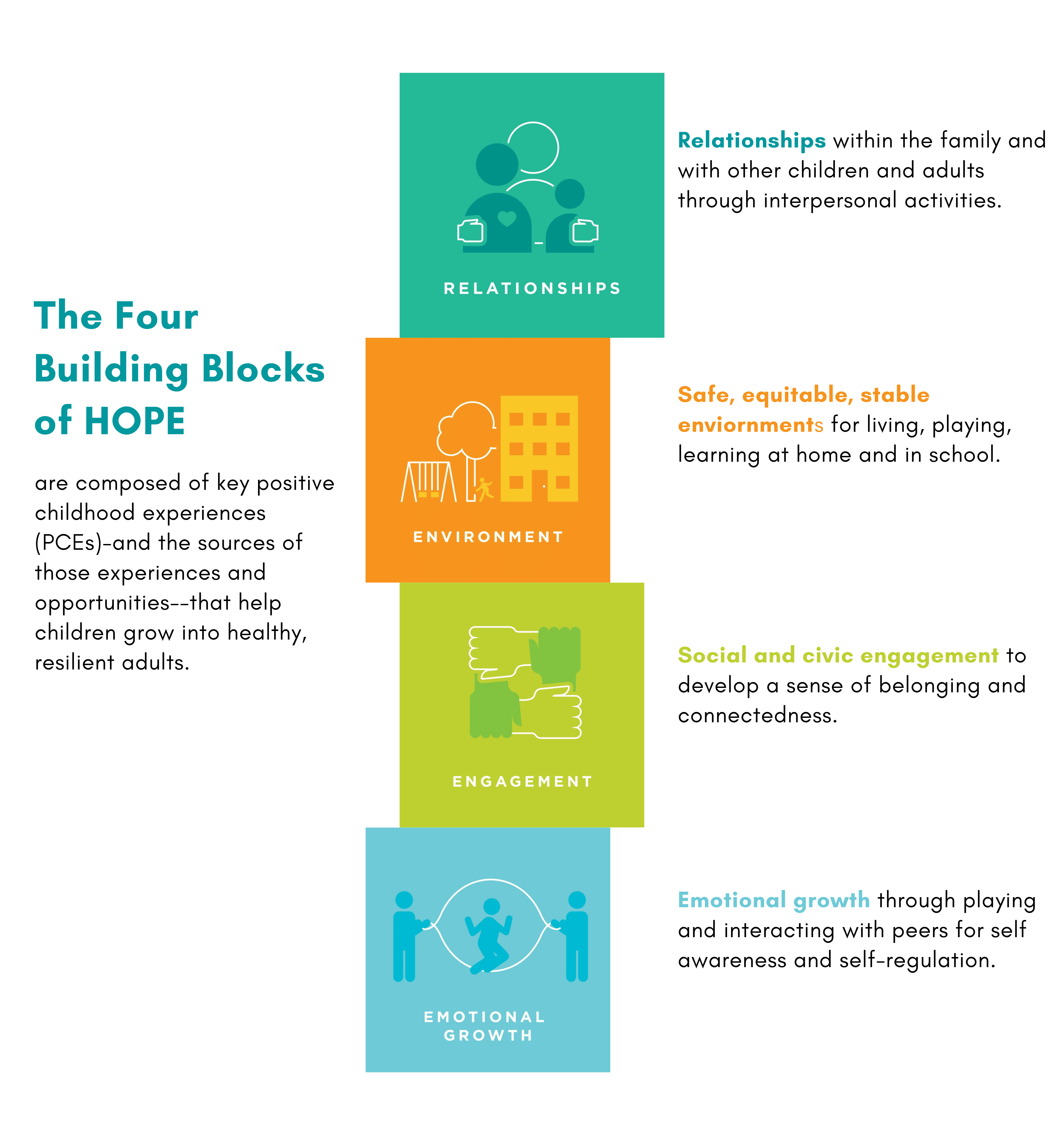

The HOPE (Healthy Outcomes from Positive Experiences) framework was developed based on these research findings. The HOPE framework centers on four building blocks: relationships with adults and other children; safe, stable and equitable environments to live, learn and play; social/civic engagement and opportunities for emotional growth.8 The HOPE framework structures the identification, honoring, and promoting positive experiences in practice. The framework promotes a relationship-based approach which transforms interactions between providers and parents, opening up dialogue to focus on a family’s assets and strength, and integrating evidence-based anti-bias skills. By focusing on the child’s experiences – similar to the focus on ACES and toxic stress, the HOPE framework adds a new dimension to the family focus of the Strengthening Families Protective Factors approach9, and the policy and norms perspective of the CDC’s Essentials for Childhood program10.

References

1. Bethell C, Jones J, Gombojav N, Linkenbach J, Sege R. Positive Childhood Experiences and Adult Mental and Relational Health in a Statewide Sample: Associations Across Adverse Childhood Experiences Levels. JAMA Pediatr. 2019:e193007.

2. Ungar M, Liebenberg, L. Assessing Resilience Across Cultures Using Mixed Methods: Construction of the Child and Youth Resilience Measure. Journal of Mixed Methods Research. 2011;5(2):126-149.

3. Kwak S, Lee TY, Jung WH, et al. The Immediate and Sustained Positive Effects of Meditation on Resilience Are Mediated by Changes in the Resting Brain. Front Hum Neurosci. 2019;13:101.

4. Dehaene S, Pegado F, Braga LW, et al. How learning to read changes the cortical networks for vision and language. Science. 2010;330(6009):1359-1364.

5. Nenert R, Allendorfer JB, Martin AM, et al. Longitudinal fMRI study of language recovery after a left hemispheric ischemic stroke. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2018;36(3):359-385.

6. Nakagawa S, Sugiura M, Sekiguchi A, et al. Effects of post-traumatic growth on the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex after a disaster. Sci Rep. 2016;6:34364.

7. Fujisawa TX, Jung M, Kojima M, Saito DN, Kosaka H, Tomoda A. Neural Basis of Psychological Growth following Adverse Experiences: A Resting-State Functional MRI Study. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0136427.

8. Sege R, Harper Brown, C,. Responding to ACEs With HOPE: Health Outcomes From Positive Experiences. Academic Pediatrics. 2017;17:S79-S85.

9. Center for the Study of Social Policy. Strengthening Families: Increasing positive outcomes for children and families. https://cssp.org/our-work/project/strengthening-families/. Published 2020. Accessed August 11, 2020.

10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Essentials for Childhood: Creating Safe, Stable, Nurturing Relationships and Environments. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/childabuseandneglect/essentials.html. Published 2019. Accessed August 19, 2020.

11. Burstein, D., Yang, C, Johnson, K., Linkenbach, J., Sege, R. (2021). Transforming Practice with HOPE (Healthy Outcomes from Positive Experiences). Maternal and Child Health Journal, 25, 1019-1024.

12. Crandall, A., Miller, J., Cheung, A., Novilla, L., Glade, R., Novilla, M., Magnusson, B., Leavitt, B., Barnes, M. and Hanson, C., (2019). ACEs and counter-ACEs: How positive and negative childhood experiences influence adult health. Child Abuse & Neglect, 96,104089.

13. Slopen, N., Chen, Y., Priest, N., Albert, M. A., & Williams, D. R. (2016). Emotional and instrumental support during childhood and biological dysregulation in midlife. Preventive Medicine, 84, 90–96.

14. Longhi D, Brown M, Fromm Reed S. Community-wide resilience mitigates adverse childhood experiences on adult and youth health, school/work, and problem behaviors. Am Psychol. 2021 Feb-Mar;76(2):216-229.